Art History

Art in Movies

From The Gilded Age to Kenwood House: How John Singer Sargent Captured America’s Dollar Princesses

If you’ve been watching the latest season of The Gilded Age, you’ll know that Gladys Russell’s engagement to the Duke of Buckingham, Hector Stanley Delaval Vere, is more than just a high-society arrangement—it’s a nod to a very real chapter of history. At the turn of the 20th century, dozens of American heiresses crossed the Atlantic to marry into Britain’s fading aristocracy. These women, often called Dollar Princesses, were wealthy, ambitious, and determined to stake their claim not just on British titles, but on culture, influence, and legacy.

Their stories aren’t just the stuff of HBO dramas—they’re etched into the grand portraits of John Singer Sargent, the painter of choice for anyone who wanted to immortalize their social ascent. A new exhibition, “Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits,” on view at London’s Kenwood House through October 5, brings these women back into the spotlight, revealing how they shaped not just high society but politics and the arts on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Dollar Princesses: More Than Just a Marriage Market

Between 1870 and 1914, at least 102 American women married into Britain’s dwindling noble families. In many cases, these marriages were transactions: new American wealth in exchange for ancient British titles. Yet these women didn’t simply become duchesses and countesses—they brought with them an assertiveness and self-belief that helped shape modern aristocratic society. They built libraries, funded charities, championed artists, and in some cases became political forces in their own right.

But how did they signal their arrival into the highest echelons of society? One of the surest ways was to commission a portrait from John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), the most sought-after society painter of the day.

Sargent and the Performance of Power

No artist captured the glittering, fragile world of the Dollar Princesses quite like Sargent. His portraits are grand, theatrical, and often quietly subversive. Far from being simple likenesses, these paintings were performances—carefully staged acts of wealth, youth, and social power.

One of the most famous examples is “Lady Agnew of Lochnaw” (1892), now housed in the National Gallery of Scotland. Lady Agnew, though not American, embodies the spirit that many of Sargent’s American sitters shared: poise, intelligence, and a subtle defiance of expectations. Her relaxed pose and direct gaze broke from the stiff formality of typical portraiture, just as her American contemporaries broke with convention in their social ambitions.

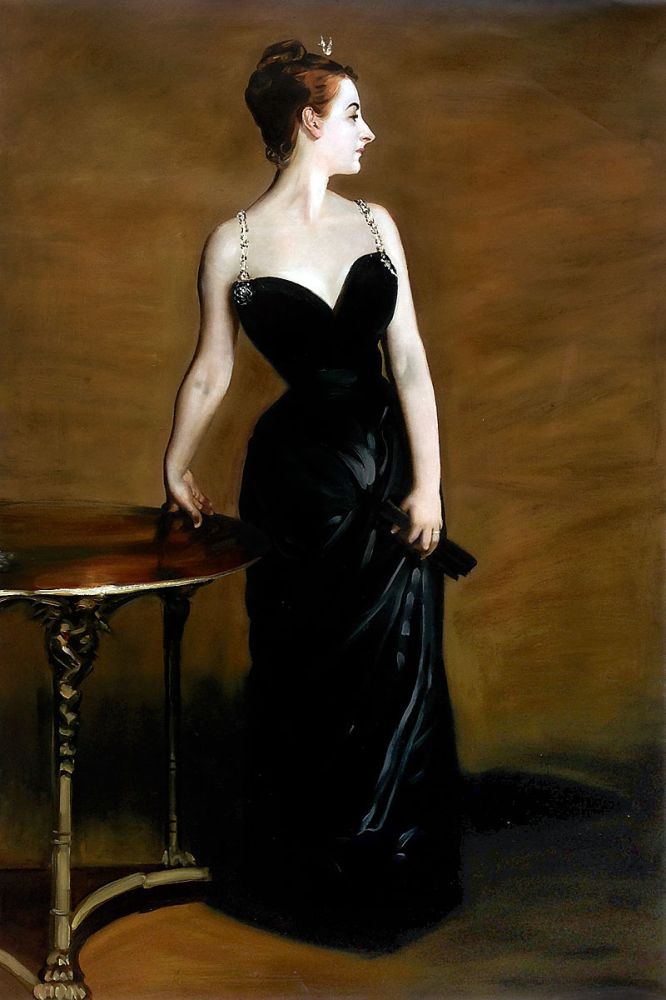

Scandal and Fame: The Madame X Affair (and Why Bertha Russell’s Choice Raises Eyebrows)

No discussion of Sargent’s career is complete without mentioning the Madame X scandal—the 1884 portrait of Virginie Gautreau that caused an uproar at the Paris Salon. With its daring composition, provocative pose, and (infamously) slipping strap, “Portrait of Madame X” nearly destroyed Sargent’s career. The scandal forced him to leave Paris for London, where it took him years to fully restore his reputation and reposition himself as the painter of choice for the world’s most ambitious and wealthy women.

Which is why, for fans of The Gilded Age, it’s especially interesting—perhaps even surprising—that Bertha Russell chooses Sargent to paint her daughter Gladys’s engagement portrait in Season 3, despite his lingering association with scandal at the time. From a plot perspective, Bertha’s choice feels bold, even calculated; she is aligning herself with avant-garde culture and artistic controversy as much as with prestige. The portrait’s unveiling at the end of Episode 3 feels less like a traditional society formality and more like a power move—a signal that the Russells intend to define taste, not simply follow it.

Art Imitates Life: The Real Gladys Vanderbilt and Sargent’s Influence on the Show

What’s clever here is how this fictional storyline mirrors history. The show’s Gladys Russell is widely thought to be inspired by Gladys Vanderbilt, the youngest daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, herself a classic Dollar Princess. The historical Gladys Vanderbilt married the Duke of Marlborough, another prime example of American wealth propping up British aristocracy. Her own portrait by John Singer Sargent, painted in 1906, shows her in a poised three-quarter standing pose—strikingly similar to the pose used for Gladys Russell’s fictional portrait on the show. Both paintings reflect the period’s fascination with wealth, restraint, and controlled glamour.

One interesting visual detail the show adds: the prominent pearl choker around Gladys Russell’s neck, absent in Vanderbilt’s portrait, but symbolically potent. Pearls, long associated with purity, wealth, and status, reinforce the portrait’s double purpose—announcing both Gladys’s arrival and her mother’s triumph.

Ultimately, while Sargent’s post-Madame X career took time to recover, The Gilded Age cleverly brings this side-story into modern cultural conversation, reminding viewers that the intersections of art, scandal, and ambition were just as relevant then as they are now.

Beyond Beauty: A Legacy of Influence

The “Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits” exhibition at the Kenwood in Hampstead London, reminds us that these women weren’t just decorative figures in grand homes. They were philanthropists, patrons, and power brokers. Their portraits serve as more than vanity projects; they’re lasting monuments to a moment when American money and European tradition collided to reshape the social order.

As The Gilded Age brings fictionalized versions of these stories to our screens, this exhibition brings us face-to-face with the real women who lived them. Through Sargent’s brush, their legacies endure—not just as beautiful faces in beautiful gowns, but as women who rewrote the rules of power, one portrait at a time.