Art

Art Reflections

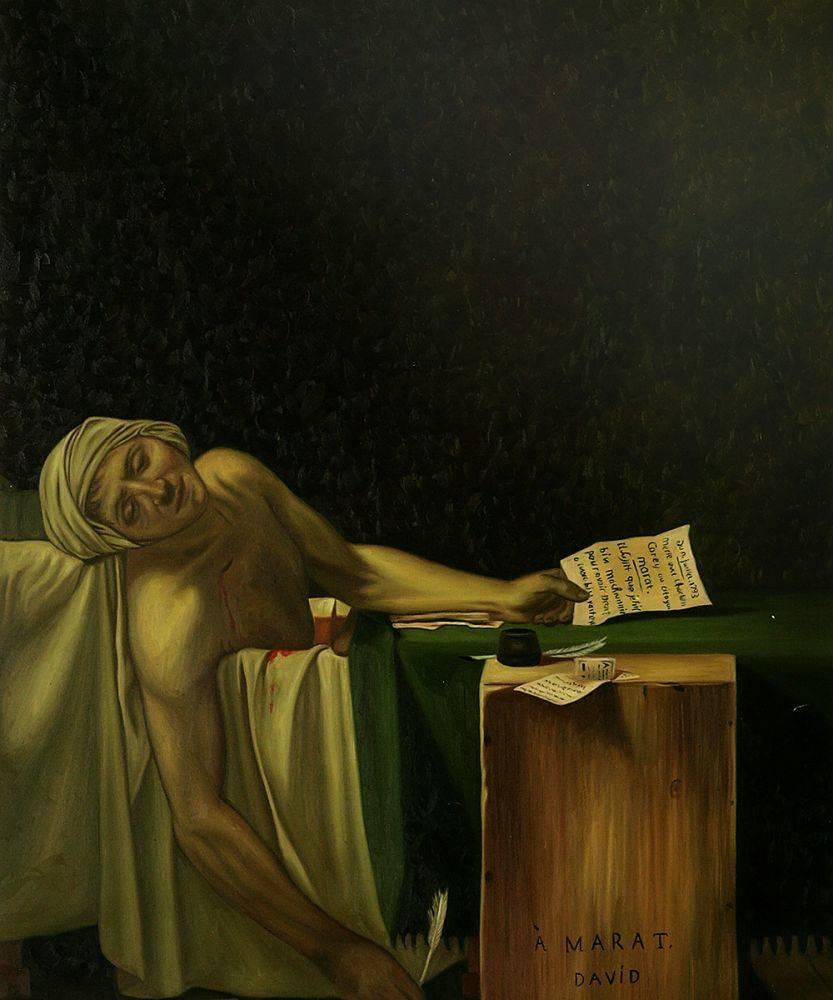

The Death of Marat: the Story Behind David’s Gruesome Masterpiece

Jacques Louis David (1748-1825) is often considered the most notable French artist during the period of the French Revolution which lasted from 1789 to 1799. He is also considered one of the founders of the Neoclassical movement that followed a more classic style than the preceding Rococo style of painting at the time, which focused on grace and light-heartedness. The Neoclassical movement, by contrast, followed the style of the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and leaned toward more historical subject matter, with dramatic and often gruesome scenes of battles or famous historical figures. David’s most famous painting, The Death of Marat, is a perfect example of one of these Neoclassical paintings of the time period. This gruesome painting features the radical French Revolutionary, Jean Paul Marat, dead in his bathtub.

Jean Paul Marat (1743-1793) was a prominent figure among the revolutionaries at the time. He was known as “L’Ami du Peuple,” or Friend of the People, which was also the title of his self-published newspaper that allowed him to spread political and philosophical ideas to the common people, also known as the Third Estate during that time period. As the revolution progressed, Marat became more radical and used the paper to attack the First and Second Estate, and the bourgeoisie, or middle class. This often got him into trouble with the law and he spent much of his time hiding in the Paris sewers or in exile in England. After being elected to the National Convention as a raging Jacobin he was able to rid the organization of the opposing Girondins, making this the height of his political career before his death.

Marat came down with a skin disease that cause eczema and lesions causing him to remain in his bathtub. While ill and near to death, he still lead, receiving and answering letters from his tub. On the evening of July 13th, 1793, a young Girondin woman, Charlotte Corday was admitted to Marat’s room. It is debated how she was able to be admitted. Some sources say she claimed to have information for him, or a list of names, and some say she said she could help protect him. Corday entered the room and stabbed Marat in the chest, a fatal wound. An uprising ensued by his followers and she was guillotined on the 17th. His death inspired a fit of rage and violence among the revolutionaries and some say that it even lead to the Reign of Terror.

David painted this depiction just days after Marat’s death, being a Jacobin himself and a follower of Marat. David as well became a prominent figure in the French Revolution, voting for King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette’s executions at the National Convention. This painting, sometimes referred to as the “Pieta of the Revolution,” became an icon among revolutionaries. Marat was considered a martyr for their cause. The image itself of course features Marat slumped over the edge of the tub with a wound in his chest. In his right hand he holds a quill he used to attack counter-revolutionaries in his journalism, and in his left, a note from Corday, that says “du 13, juillet, 1793. Marie anne Charlotte Corday au citoyen Marat. Il suffit que je sois bien malheureuse pour avoir droit à votre bienveillance,” which reads in English, “Of 13 July, 1793. Marie Anne Charlotte Corday to Citizen Marat. It is enough that I am very unhappy to be entitled to your benevolence.”

After the revolution, David was sent to prison along with many other revolutionaries. When we was released he began teaching other prominent artists such as, Ingres and Gerard. Later David would go on continuing to paint historical images, such as the Coronation of Napoleon and Napoleon Crossing the Alps.